In 1871, Colt employee Charles Richards was awarded a patent for converting Colt percussion models to breech loading cartridge revolvers. The Richards cartridge conversion was an instant success. On July 2, 1872, William Mason, another Colt employee, was awarded a patent for an improvement to the Richards model. Conversion models remained popular with cowboys (many originals will be found with imprints of fence staples on the butt) even after the introduction of the 1873 Colt®. This was due to the low cost of conversion models. Use continued long after more modern cartridge revolvers were introduced.

In 1959, Aldo Uberti began making replicas of Civil War-era cap and ball revolvers. He founded A. Uberti S.R.L. in the village of Gardone Val Trompia in the Italian Alps. Over the years, as his craftsmen gained experience, the company increased production by including more and more of the Old West firearms. Uberti reproduction firearms were instrumental in providing firearm for many a “Spaghetti Western” and that sparked a growth in “period correct” firearms for us lovers of these firearms.

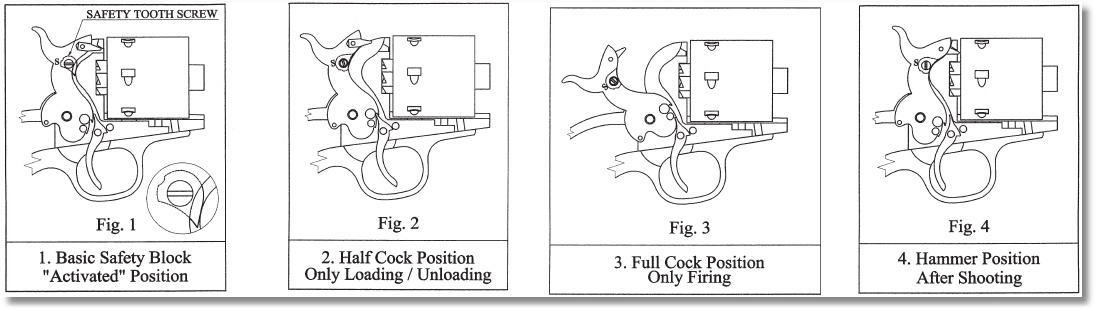

Uberti firearms are exacting replicas, down to the finest detail. Many are improvements over the originals, with the advancement of materials and the use of modern machinery. With the 1871 Navy Colt Conversion replica (and others), Uberti remained true to the Richards-Mason cartridge conversion, but has added a safety bock in the hammer, which can be activated or deactivated by the turn of a simple screw, to bring the firearm up to modern safety standards.

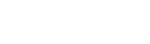

The Uberti 1871 Colt Navy Open Top Conversion revolver (model 341356) sports a 5.5 inch round barrel. Another model is available with a 7.5-inch barrel. A case-hardened frame matches up nicely with the brass back strap and trigger guard and to the blued-steel barrel assembly. The brass back strap and trigger guard lends a nice contrast with the rest of the revolver and when matched with some highly polished walnut grip panels, the overall revolver is very stylized and sleek looking. As part of the conversion to cartridges from percussion revolvers, the 1871 Colt Navy Open Top Conversion revolver has a spring-loaded ejector rod that assists in ridding the revolver of spent cartridges. Similar to the ejector rod used on later 1873 Colt “Peacemaker” revolvers, the ejector rod is on the right side of the barrel (secured by a heavy screw in the frame) and has a small lever that must be first rotated upward and then rearward to expel the spent cartridge. A loading gate keeps the rounds within the cylinder and a simply push of the tube outward releases the loading gate.

Loading gate and Six Round Cylinder of .45 LC Ammunition. Note use of A-Zoom Snap Caps for Dry Firing and Storage. Also Note Rear Site Notch on Rear of Barrel

The cylinder, unlike that found on the 1858 Remington New Army conversion, does not have recessed chambers; there is a gap between the rear of the cylinder and the frame. This gap allows the shooter to instantly see if the firearm is loaded. The cylinder locks up tight and there is absolutely no play front-to-rear or side-to-side. This revolver is tightly fitted and that is a testament to the quality, while not perfect, of Uberti reproductions.

The cylinder of this revolver is engraved with a scene of the victory of the Second Texas Navy at the Battle of Campeche on May 16, 1843, just like the original and is not fluted, which adds strength to the cylinder. Chamber thickness is about .047 inch, so no, this is not a Ruger and ammunition should be selected to compliment the firearm and not destroy it. For 230-grain .45 LC ammunition, I like to stay around the 850 fps velocity if not under, which is a comfortable load to shoot. If I want to run hot loads, I’ll go to the Ruger Blackhawk. The hammer, as mentioned before, incorporated a safety block that is operated by the turn of a screw. The screw can only be seen when the hammer is in the half-cock or fully cocked positions. Although the block safety does move away from the original design, I have come to not notice it all.

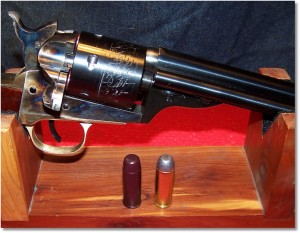

Dry Firing Without Snap Caps Is Not recommended. A-Zoom 45 Colt Snap Caps (On Left) Are Perfect To Use for Dry Firing and Storage And Are Exactly The Same Dimensions of Live Ammunition (On Right)

It is not advised to dry-fire this revolver and use of snap caps is highly recommended. I use those by A-Zoom for dry-fire and when storing the firearm. You can see those chambered in the firearm in the accompanying image.

There is absolutely no take-up in the trigger and (on this particular model) the trigger breaks crisply at a hair over three pounds with just a hint of over-travel. As the trigger in my revolver wears in, I am sure that it will smooth out and become lighter still.

With Practice, the Entire Revolver Breaks Down Faster than Field Stripping a 1911 Pistol. There is no need to go further than this.

Substantial Cylinder Support. Note Slot for Barrel Wedge. Lubriplate NO. 130-A Coats the Cylinder Rod.

Surprisingly, the revolver is nicely balanced.

The brass back strap and trigger guard is a two piece unit that is attached to the cold-steel frame by six screws. A single screw mounts the back strap to the trigger guard. On the left side of the revolver, just behind the trigger guard, the caliber of the firearm is stamped. The firearm’s serial number is stamped on both the frame and the brass just beneath the cylinder at the front. 1871 is stamped into the frame just above the disassembly wedge. Also and just below the cylinder on the left side of the frame, the frame is marked with the so-called “Two July” patent marking, also found on the 1851 Navy-, 1861 Navy- and 1860 Army-conversion revolvers. The “Two July” patents were also found on very early Colt Single Action Army revolvers. The top of the barrel is stamped with manufactures stamps. In addition, the caliber is stamped under the barrel just rearward of the ejector rod “button”, which in this case is CAL.45 LC. Sights on the 1871 Colt Navy Conversion are quite unique. The front sight is a fixed bladed sight that is inset on the front of the barrel while the rear sight was unique to the 1871/72 Colt Navy. The rear sight is a raised notch at the rear of the barrel near the forcing cone. Since the 1871 Colt Navy was an open-top revolver there were not too many choices to provide a rear sight. On some open-top revolvers, there was a sighting notch cut into the hammer; when the hammer was at full cock, the front sight was aligned with the rear sight – the hammer. With the 1871 Colt Navy, the front sight is aligned with the raised rear notch. The front sight and the rear notch are very thin. These were more instinctive shooting firearms than target revolvers; simply point the barrel in the right direction and pull the trigger. However, it is surprising how accurate these firearms can be when time is taken to actually use the sights. Although this revolver is available in .38 special, .45 LC is my preferred chambering and is quite impressive from the business end of the revolver.There are some imperfections in the brass with my particular revolver, but this is not a show piece and I can live with them. If I can’t, I know how to remove the imperfections but they take no quality away from the piece. The brass does polish up nicely with some Flitz polish.

RANGE DUTY:

Folks unfamiliar with revolvers of this nature discount them because of their supposed poor accuracy. Nothing could be further from the truth; they are as accurate as any modern firearm at “combat distances” and beyond.

As with the 1858 Remington New Army Conversion by Uberti, I traipsed over to the range immediately after purchasing the 1871 Colt Navy conversion revolver. I still had some PROGRADE .45 Colt 250-grain Cowboy Grade ammunition left over from a previous shoot and decided to put twelve more downrange for function testing. A simple target was posted at fifteen yards, as I had done with the 1858 Remington New Army Conversion, and I wanted to see how the 5.5 inch barrel of the Navy would fare against the 8 inch barrel of the Remy conversion.

I am in the habit of firing SA revolvers from a standing one hand position. Dropping the sight picture to a six o’clock hold and trying to concentrate on the very narrow front sight and rear channel, I put six shots pretty close to the center. Another round of six rounds was fired and I have to say that the accuracy of the 1871 Colt Navy was on par with the 1858 Remington New Army conversion. The muzzle lift was a little more pronounced due to the shorter barrel on the Navy but I was more than satisfied with the result. I was expecting much more flash from the top of the forcing cone, due to the revolver not having a top strap, but was surprised how little side flash there actually was. Perhaps, it was due to the tight forcing cone-to cylinder or simply the shape of the outside of the barrel at the forcing cone. At this point I really don’t know. What I do know is that when I placed the sights at 6 o’clock on the target, 45 caliber holes starting appearing just above the POA. Let’s just say that with an IDPA target, all shots were within the center and head -0 areas. That’s not bad for a reproduction revolver.

As a side note, a fella a few lanes over from me was working out a semi-automatic pistols. He was shooting two-handed strings anywhere from two to four rounds fast fire. I checked his target after he fired, and out of the multiple rounds fired only three were in the bull. I fired six rounds during his shooting; six rounds in a 5″ group centered in the -0 area while shooting one-handed. I’m not bragging on my shooting, but I am saying that sometimes we need to slow down to shoot accurately.

What I do know is that the 1871 Navy Colt Conversion (Early Version) by A Uberti is a fine piece of work, it is a natural pointer for me, and accurate enough to make me want to shoot it more – unlike some other “replica” firearms I have shot in the past. The 1871 Navy Colt Conversion also looks great and fits well into a Hunter Cross-Draw Slim Jim Holster.Shooting should be fun when we are not training for self-defense, and shooting a fine replica of a single-action revolver that was used by many well after the famous 1873 Colt Peacemaker makes it happen. After all, who can turn down the chance to fire a revolver made famous by famous users including; Wild Bill Hickok, John Henry “Doc” Holliday, Richard Francis Burton, Ned Kelly, Bully Hayes, Richard H. Barter, Robert E. Lee, Nathan B. Forrest, John O’Neill, Frank Gardiner, Quantrill’s Raiders, John Coffee “Jack” Hays, “Bigfoot” Wallace, Ben McCulloch, Addison Gillespie, John “Rip” Ford, “Sul” Ross and most Texas Rangers prior to the Civil War and (fictionally) Rooster Cogburn.

I know that Uberti has a firearm just waiting for you. For me, I want to add two more reproductions to the mix when and if funds allow (Author’s Note: I was able to purchase this revolver for $100 with a trade-in of one of my rarely shot more modern pistols.):

- Uberti 1875 Army Outlaw, a Remington reproduction in .45 LC and 7.5-inch barrel. I like the 1875 Remington over the 1873 Colt Army revolver for a couple of reasons; it became the underdog once Colt introduced the 1873 “Peacemaker” and I feel that the 1875 Remington was superior to the 1873 Colt in several ways. That’s just me.

- Uberti 1873 Colt Cattleman, .45 Colt, and with the original length 7.5″ barrel

SOURCES:

for information on Uberti products, Visit: http://www.uberti.com/

A-Zoom Snap Caps (dry fire and storage), visit: http://www.azoomsnapcaps.com/home/

![]()

Pingback: Rediscovering (Early) Revolvers | Gun Toters