When most folks start talking double-action revolver speak, it is usually in reference to a Smith & Wesson, Colt, Ruger, or possibly even Taurus.

My first double-action revolver was a Rohn RG38. Around that time (1970), the RG38 was considered a ‘Saturday Night Special’ at best. But, it was all I could afford when I got my first CC permit in the State of Georgia. Also, I was in the military and knew that I would have to deploy (again) at some time and would need to sell the firearm quickly; cheaper firearms are easier to sell than more expensive ones. Regardless, the RG38 was carried on the body in the best holster I could afford, which means that it wasn’t a holster at all, simply a placeholder. However, the RG-38 served me while. And, while never fired in anger it was certainly fired in frustration. The trigger pull was such that my trigger finger grew larger in girth than other fingers on the same hand; it was akin to pulling a boat trailer (with boat) on a string attached to the trigger finger.

Fast forward to my return to the ‘World’ and was able to afford a better revolver and opted for a Smith & Wesson model 36, which was a fine revolver and was my constant companion until I decided to go the 1911 route. I held on the Model 36 for many years until I had to part with it during a financial crisis.

Double-action revolver design has not evolved much over the years. Or, should I say that semi-automatic pistols became the precedence and the revolver somewhat languished in obscurity, although many people still favored the revolver because they simply worked and did not suffer from some of the ills of pistols. Magazine capacity became a concern and with pistols like the Browning Hi-Power, CZ75, and Beretta 92 leading the pack in capacity, the revolver was not only pushed out of the pack, but was disregarded as a poor choice for self-defense carry. A great many; however, still favored the lowly DA revolver.

Of the few changes to the revolver, lightweight models seemed to be in some favor due to their being, well, lightweight. That is, until you actually had to shoot one with even modest loads. My old Smith & Wesson Model 36 was a handful to shoot even with standard 158-grain SWCHP ammunition. Weight, sometimes, is a good thing.

When Sturm, Ruger & Co. introduced the SP101 in 1988, my interest in compact revolvers increased, but it took quite a while to act on that interest. Eventually, a SP101 KSP-321X (.357 magnum with 2.25-inch barrel) found its way into my carry routine. The weight of this little “tank” (as it was often referred to), made the compact SP101 mostly pleasant to shoot with modest loads, and with 125-grain .357 magnum ammunition going out the muzzle the SP101 was still manageable while the flame at the front end was as impressive as the recoil. But, again, I opted for the 1911-based pistol as my primary carry – and have ever since. While most other DA revolvers (including a Smith $ Wesson Model 686, two Taurus Model 36s, and Dan Wesson Model 715) were sold, the Ruger SP101, a Ruger 4.2-inch GP100, and a Ruger 5-inch GP100 is all that remained of my DA revolvers – until now.

As I mentioned, I think that DA revolvers took a dive in interest among shootist in much same fashion as single-actions revolvers fell from favor in favor of double-action revolvers. Although many still liked the SA and DA revolvers, many felt that the higher capacities of the semi-automatic pistols were the best means to defend yourself and the homestead in general. While the revolver may no longer be the mainstay of self-defense these days, that is not to say that the revolver ready for extinction; it is still evolving, but just at a slower pace. The recent introduction of the Kimber K6S is a testament to the fact that DA revolvers are still evolving.

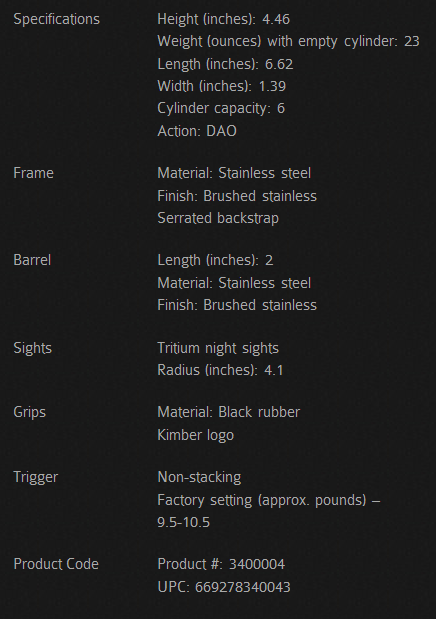

I handled, but had not shot, a Kimber K6S when one arrived at my local gun club and range some time ago. The K6S had some features that I really liked; it was DA only (no protruding hammer spur to catch on clothing), Tritium night sights front and rear, recessed cylinder chambers, brushed stainless steel finish, excellent fitting rubber grips, an unfluted cylinder, and most of all – six shots were available (as compared to most ‘snubby’ revolvers of this size that have a five shot capacity.

I handled, but had not shot, a Kimber K6S when one arrived at my local gun club and range some time ago. The K6S had some features that I really liked; it was DA only (no protruding hammer spur to catch on clothing), Tritium night sights front and rear, recessed cylinder chambers, brushed stainless steel finish, excellent fitting rubber grips, an unfluted cylinder, and most of all – six shots were available (as compared to most ‘snubby’ revolvers of this size that have a five shot capacity.

The frame and barrel is forged stainless steel, and it is nicely forged stainless steel. The K6S is one of the nicest finished that I have seen in a long time. All edges are beveled to provide the smoothest profile as possible. The trigger face is rounded The right side plate is held in place by an Allen screw and the seam is so well finished that you won’t notice it unless you are looking close at it. The cylinder is locked into place solidly at the front and rear; when the cylinder is closed, it is definitely locked up. Pull the trigger all the way to the rear and hold it, then try to move the cylinder, and you will feel no perceptible play.

The frame and barrel is forged stainless steel, and it is nicely forged stainless steel. The K6S is one of the nicest finished that I have seen in a long time. All edges are beveled to provide the smoothest profile as possible. The trigger face is rounded The right side plate is held in place by an Allen screw and the seam is so well finished that you won’t notice it unless you are looking close at it. The cylinder is locked into place solidly at the front and rear; when the cylinder is closed, it is definitely locked up. Pull the trigger all the way to the rear and hold it, then try to move the cylinder, and you will feel no perceptible play.

Kimber may have borrowed a few things from Ruger, which makes this revolver (almost) as robust as the Ruger SP101. One of those items is the cylinder latch. Unlike Colt (pull to the rear) or Smith and Wesson (push to the front), the K6S incorporates a ‘press in’ cylinder release much like the Ruger DA revolvers. The cylinder latch button incorporates a checker-board pattern that assures positive engagement. The second item that I really like is the trigger. The reason is that it is a close to a Ruger DA revolver trigger that can be found.

Kimber claims that the trigger is a ‘non-stacking’ trigger. Stacking is when the resistance of the trigger increases through the pull. Some triggers have a noticeable step in their resistance, but with others the increase is more gradual. In either case, this should occur consistently both in the amount of resistance and where it’s encountered in the trigger pull. ‘Stacking’ and “Staging’ are not the same and the two terms are often confused. ‘Stacking,’ as explained refers to the amount of resistance felt throughout the trigger pull. In short, a trigger where the resistance is the same throughout its travel is a non-stacking trigger. However, that trigger pull reaches a point where the ‘stacking’ decreases. The DAO trigger pull; incidentally, is between 9.5 pounds and 10.5 pounds. The trigger pull on my K6S hits pretty close to the middle and I expect it to lessen as the revolver breaks in. There is absolutely no grit to this trigger moving rearward and fast shots are just as smooth as slow shots. On the return trigger stroke, it feels like it is gritty but it is not, it is simply everything internal resetting.

‘Staging’ a trigger entails you grabbing the revolver in a standard firing mode, but you work your trigger really quick to the rear and that will index the cylinder fully and it will cock the hammer about three quarter of the way and with the last of the trigger pull. This could be referred to as a ‘slack’ point, but most refer to it as the ‘staging’ point. At this ‘staging’ point, get a perfect sight of an alignment, and press the trigger straight to the rear. This technique is really good on a hard shot or a long range target. It takes up about three quarters of the trigger pull and all you have to do is finish it off and make a real accurate shot. Some revolvers have ‘staging’ points that are hard to detect, but Ruger DA revolvers seem to have a very discernible ‘staging’ point. The fact is that you can hold this point for virtually any length of time that you want. The ‘staging’ point in a DA revolver, as a comparison, would be similar to that of a compound bow; the initial pull is heavy and then the bow reaches a point where the pull is extremely light. In summary, for rapid fire you’ll want your finger right on the face of the trigger, just using the pad. For slow fire, and for a little bit more accurate shot, you might want to put your finger through a little bit and stage it. My trigger finger is set in just before the first joint (I have long fingers).

A small revolver is not known for accuracy, because of the short sight radius. Working the ‘staging’ point allows you to ensure that the sights are in alignment throughout that last very short pull of the trigger is performed before the hammer drops.

Moving on the sights, I can only say that they are excellent. Most folks these days favor night sights and the K6S comes standard with them. The front sight is pinned while the rear sight is dovetailed into the frame. Again, with the rest of the revolver, there are no sharp edges on the rear sight. The dot on the front side is larger than the two dots on the rear sight, which makes for quick sight alignment.

The grips are rubber from Crimson Trace, have some cushion to them, and also a palm swell. One of the first things that I change on a small revolver is the grip, as they are usually too small for my hand and I struggle to get the revolver in place and hold it there while shooting. When I changed the grips on my SP101, I opted for a nice set of exotic wood grips from Hogue. After shooting some full-power .357 magnum loads through it, the grips were quickly swapped with Hogue rubber grips and shooting became a lot more pleasant. The grip of the K6S has a finger groove, which helps to position the hand correctly. The width of the grip is tapered from top to bottom and provides as much rubber to the palm of the shooting hand as possible without going overboard on grip width. The back strap is devoid of rubber, but incorporates vertical grooves. The back strap is such that you can achieve a very high handhold on the grip, which is essential to controlling a small revolver like this. The other beauty of the K6S is the lack of an external hammer that could catch the web of the hand for some where that part of the hand is, well, fleshy like mine (I have found no exercises that firm up that part of the hand). Not having to worry about hammer bite is something I always enjoy. The reach to the trigger is short, as can be expected from a compact revolver. However, the face of the trigger finds itself nicely nestled in the first joint of my trigger finger – right where I like it.

The grip is held in place by a single screw and is of the pinky-hanger type; your pinky is going to hang off of the grip. But, that’s alright because that pinky wraps under the grip nicely. With the pinky finger beneath the grip, the support hand presses that pinky into the grip. The thumb of the support hand comes over top of the shooting hand thumb and the next thing you know is that you have a very solid grip on a very solid revolver.

The grip, as the rest of the K6S, fits and functions perfectly. I feel no need to change grips – until a better grip is found.

The ‘Flash Gap’ (the distance from the cylinder face to the throat of the barrel (the forcing cone) is less than 0.002-inches. And, because of the recessed cylinder chambers, the clearance between the rear of the cylinder and the recoil shield seems just as close as the ‘Flash Gap.’ And, speaking of the cylinder, the cylinder on the Kimber K6S and incorporates ‘flats’ over ‘flutes’ in its design. The ‘flats’ add strength to a cylinder capable of holding six cartridges rather than five cartridges as is common among short-barreled, small-frame revolvers.

Unlike the Ruger SP101 (and other Ruger revolvers) the K6S cylinder lock-up is in the conventional fashion; at the rear of the cylinder and at the ejection rod; whereas, the SP101 is at the rear of the cylinder and at the front of the crane, which attributes to the Ruger ruggedness (note that Dan Wesson revolvers latch at the front of the crane, which contributes to the hardiness of these revolvers). However, that is not to say that lockup on the K6S is weak. Due to the recessed chambers of the K6S, there is very little gap between the base of the cartridges and the recoil shield, which minimizes rearward movement of the cartridges under recoil. Regardless, I don’t see running a continuous diet of full-house magnum ammunition in the K6S revolver being beneficial to the life-span of the K6S (or any revolver for that matter) or the shooting hand, unless you just particularly enjoy having a flamethrower with very high recoil energy in your hand.

The last item worthy of mention is the angle of the rear of the frame in the hammer area. When you think of ‘hammerless’ revolvers (which is a misnomer and is actually a ‘shrouded hammer’ or Double Action Only (DAO) revolver), you may hearken back to the Smith & Wesson Model 649, (or ‘Body Guard, as it came to be known). Taurus made a ‘shrouded hammer’ revolver, as well. Ruger also makes a SP101 ‘Shrouded Hammer’ version with it Model 5720. The S&W 649 hammer shroud was likened to a ‘Hunchback;’ whereas the hammer shroud on the Ruger SP101 5720 kept the lines of the ‘traditional’ revolver design. The Kimber K6S; however, broke the mold and is one of the finest examples of ingenuity in streamlining the hammer area. The rear sight blends perfectly into a declining slope at the rear of the revolver’s frame into a sheer vertical wall in which to rest the web of the shooting hand. You could actually fire the K6S with your thumb atop of the hammer shroud and use the tip of your thumb as a pointing device on the backside of the rear sight or just below it. As Doctor Spock would say, “Fascinating!”

Regardless of how a firearm looks or feels, the telling point is how it performs. Watching Hickock45 in his video shoot the Kimber K6S and hitting the 80-yard going with it several times told me two things; I am not Wild Bill Hickok nor am I Hickock45. My challenge was simply place bullets on a target at ‘combat’ distance (seven yards) with some degree of accuracy. If I were to carry the K6S, I would probably be carrying .38 Special +P ammunition – maybe. Since the local gun club and range has some Sig Sauer .38 Special 125-grain, +P V-Crown JHP, a box was purchased for evaluation purpose. Added was some standard pressure 158 Grain SWCHP that was the preferred LEO cartridge in my day, and a few 125 Grain .357 magnum cartridges (rated as the best all-around .357 magnum cartridge) that had caused me to change grips on the Ruger SP101 from wood to rubber. Given that there is only a three ounce difference in firearm weights (23 ounces for the K6S vs. 26 ounces for the SP101) and is probably due to the 2-inch barrel vs. a 2.25-inch barrel of the SP101, and the fact that I had one more cartridge than the Ruger SP101 to play with, it was going to be an interesting shooting experience.

Regardless of how a firearm looks or feels, the telling point is how it performs. Watching Hickock45 in his video shoot the Kimber K6S and hitting the 80-yard going with it several times told me two things; I am not Wild Bill Hickok nor am I Hickock45. My challenge was simply place bullets on a target at ‘combat’ distance (seven yards) with some degree of accuracy. If I were to carry the K6S, I would probably be carrying .38 Special +P ammunition – maybe. Since the local gun club and range has some Sig Sauer .38 Special 125-grain, +P V-Crown JHP, a box was purchased for evaluation purpose. Added was some standard pressure 158 Grain SWCHP that was the preferred LEO cartridge in my day, and a few 125 Grain .357 magnum cartridges (rated as the best all-around .357 magnum cartridge) that had caused me to change grips on the Ruger SP101 from wood to rubber. Given that there is only a three ounce difference in firearm weights (23 ounces for the K6S vs. 26 ounces for the SP101) and is probably due to the 2-inch barrel vs. a 2.25-inch barrel of the SP101, and the fact that I had one more cartridge than the Ruger SP101 to play with, it was going to be an interesting shooting experience.

While I am not going to go into detail, I can say that shooting the Kimber K6S was a rewarding experience in that I learned what not to shoot through this revolver. If I did my part, the K6S did its part and I was able to keep the majority of rounds within a 3-inch circle at the “combat’ distance of seven yards; albeit, slightly to the right of point-of-aim. That could have been me or the sights. Luckily, the rear sight is drift adjustable for windage, and a slight tap left on the rear sight would probably prove beneficial (in my case). However, another shooter of the K6S was shooting slightly left. For the time being, I am leaving the rear sight where it is, as a slight-right impact at ‘combat’ distance is not going to be show stopper and I know how to compensate for it.

Recoil is straight back into the hand with the web of the shooting hand taking the brunt of the recoil.

- Shooting the 158-grain SWCHP ammunition was a breeze. The recoil, while stout, is highly manageable.

- The 125 Grain +P ammunition was, of course, a little stouter, and after a cylinder full the shooting glove was put on. I like the nerves in my hand enough to try and protect them as much as possible. Muzzle flash is also much greater than with standard loads.

- The 125-grain .357 magnum stouter still almost to the point of being extremely abusive to the hand. Only three magnum loads were shot, but they were right on target. My shooting companion shot a video of me shooting the magnum loads, and the flame out of the front of the barrel is impressive to say the least. Yes, Martha, the 125-grain .357 magnum ammunition is a heck of a flamethrower out of a 2-inch barreled revolver. With a good grip on the gun, I was able to return the barrel on target very quickly, however.

My ammunition recommendation for the K6S is the simple, reliable, time and performance proven 158-grain SWCHP or even LSWC in standard loading. In fact, that is my standard ammunition recommendation for any small frame, short-barreled revolver. A few examples would be the Hornady 158-grainJHP/XTP (38E) @ 800 fps, The Hornady 125-grain JHP/XTP (90332) @ 900 fps, or the Federal 110-grain Hydra-Shok (PD38HS3H) @ 980 fps. Note that the majority of velocities are referenced to a 4” barrel. BBTI (http://ballisticsbytheinch.com/38special.html) shows the Federal 125-grain Hydra-Shok JHP at about 700 fps out of a 2-inch barrel. The Speer 125-grain GDHP is rated at 860fps in the 5th Edition of Ammo and Ballistics, but the Speer 135-grain GDHP is rated at 766fps out of a 2-inch barrel, according to BBTI. Bottom line here is that a lot of velocity is going to be lost from standard velocity figures with a short-barreled revolver and ammunition choices may be critical.

Leave the +P ammunition for the big guns. What little advantage that you gain in velocity with a short-barreled revolver shooting +P ammunition is not worth the price to pay in recoil and reduced control. Just because a handgun is rated for .357 magnum ammunition does not mean that it is the best cartridge to shoot.

A neat little trick that I found while shooting the K6S is that I can place the thumb of my shooting hand on top of the “hammer shroud” while using the tip of my thumb as a pointer to align with my target, although the thumb does cover the rear sight. The thumb also serves as a means to help control muzzle jump, keeping the dangerous end of the firearm pointed in the right direction for quick follow-up shots.

Some might question carrying a ‘snubby’ DAO revolver as a primary self defensive firearm. Most would be concerned with capacity. For reloading, both speed loaders and speed strips are available for the K6S. Personally, I like speed strips for partial reloads and speed loaders for full reloads and have used both in LEO ‘Bull’s-eye’ revolver competitions. The Kimber K6S comes with one speed strip from Desantis Cowhide; however, I prefer those from Bianchi. I am used to carrying two spare eight-round magazines for a 1911 and I don’t feel that I am giving up a thing with two speed loaders on the belt and a couple of speed strips in the pocket (for extra measure).

The Kimber K6S Fits Within a Cross Breed Super Tuck Holster Intended for the Ruger SP101. (Note that I later removed the sweat guard.)

While some would say that the Kimber K6S, because of its design, might qualify as a ‘pocket pistol’ I see it more as an IWB carry on my strong side where it needs to be. I had purchased a Cross Breed Super Tuck IWB holster for the Ruger SP101 quite some time ago. Fortunately, the Kimber K6S is right at home in the same holster for the Ruger SP101; albeit, a slightly looser fit than with the SP101. The Cross Breed Super Tuck (CBST), as all my IWB holsters has had the sweat Guard surgically removed so that there is absolutely no interference in getting to the grip of the firearm. I have also set the height adjustment so that as much of the holster as possible is within the pants. The cant of the holster has also been adjusted to my liking. With that said, I have ordered a CBST specifically for the Kimber K6S and will also modify it to my taste. While the profile of a CBST for a small frame revolver would seemingly be somewhat greater than for a semi-automatic pistol, the profile is, in fact, no worse than a CBST for a Springfield XDm 4.5 .45acp or even a Glock G19. As a side note, if you adjust the cant on the CBST, it also makes an effective IWB cross-draw holster.

As another side note, when you are carrying any short-barreled firearm IWB, the stability of the holster within the pants is of the utmost importance. Short barreled firearms do not have enough barrel length and, in many times, have a tendency to “roll” out of the carry position. I have had this happen on several occasions with holsters that do not have adequate support on the belt or inside the pants. What this means that you end up adjusting the holster when you should not have to. The wider the holster mounts, the more stability your carry will have, and the less you have to fiddle with the holster. The holster should be an integral part of your wardrobe and not just something attached for convenience.

To wrap this entire thing up, I can say that the Kimber K6S is a DOA revolver well worth the price. At the time of this writing, a Ruger SP101 (Model 5718) is going for $719 MSRP; whereas, the Kimber K6S is $912. However, both can be found for less if you shop wisely. The Kimber K6S has proven itself worthy of carry and probably will be carried at some point in my seasonal rotation; albeit, it will be carried with .38 Special ammunition and not with .357 magnum ammunition.

For a first attempt of a company famous for making quality 1911 pistols, Kimber has done it right coming out of the gate with a compact DAO revolver. The entire firearm reeks of innovation, is very pleasing to look at, definitely pleasing to shoot, and that is something that is desperately needed in revolver design (I won’t even mention the Chiappa). I have absolutely nothing negative to report on the Kimber K6S revolver.

If you are on the fence about which ‘Snubby’ to buy, for example; a Ruger SP101 or the Kimber K6S, here are two videos to views for comparison sake:

Hickock45 – Ruger SP101: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4PGOyvafwo

Hickock45 – Kimber K6S: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8RQAGX967bg

And this one from TheFirearmGuy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kghxlqhkSZ4

There is also this review on the Kimber K6S: http://blog.cheaperthandirt.com/range-report-kimber-k6s-revolver/

Of course, there is one stark difference between the Ruger SP101 and the Kimber K6S and that is the number of calibers for each revolver. For the Kimber K6S, at the present time, there are only two calibers to select from; .38 special and .357 magnum. The caliber advantage obviously goes to the Ruger SP101, which is chambered in .38 special, .357 magnum, .327 magnum, 9mm, and also in .22 LR. Barrel lengths for the Ruger SP101 also exceed that of the Kimber K6S with 2.25-inch, 3-inch, and 4-inch barrel lengths. With that said, if the acceptance of the Kimber K6S grows, more barrel lengths and calibers may be possible at some point in the future? However, I feel that Kimber is simply saying that we can build a DAO revolver with the same quality and care as we do our 1911 pistols.

The Ruger SP101 and Kimber K6S are made in the U.S. products, and that I find appealing. While the Ruger SP101 has been around quite a while and has proven itself to be an excellent compact revolver, the Kimber K6S is first generation and may have to prove itself among revolver enthusiast. But, I don’t think that will be a problem, as the Kimber K6S is one fine revolver that is highly comparable to the rugged, and highly-reliable Ruger revolvers.

Finally, and to tell the truth, if the only choice that I had for a compact revolver with a shrouded hammer came down to the Ruger SP101 (5720) and the Kimber K6S, it would be a tough decision. While not taking anything away from the Kimber K6S, my choice would probably be with the Ruger SP101. Aside from the obvious price difference between the two revolvers, the Ruger SP101 can be outfitted with a Hogue rubber grip that really tames the recoil and handling of the revolver. At the time of this writing, only wood grips are available for the Kimber K6S and I do not want to shoot this revolver with wood grips with any load.

Finally, and to tell the truth, if the only choice that I had for a compact revolver with a shrouded hammer came down to the Ruger SP101 (5720) and the Kimber K6S, it would be a tough decision. While not taking anything away from the Kimber K6S, my choice would probably be with the Ruger SP101. Aside from the obvious price difference between the two revolvers, the Ruger SP101 can be outfitted with a Hogue rubber grip that really tames the recoil and handling of the revolver. At the time of this writing, only wood grips are available for the Kimber K6S and I do not want to shoot this revolver with wood grips with any load.

![]()