Matt Dillon (James Arness) of the T.V. series “Gunsmoke” had a long one. History has stated that Wyatt Earp supposedly had an even longer one. Wild Bill Hickok had a normal-sized one, while Bat Masterson and Doc Holiday had shorter ones.

I don’t know what you are thinking, but I was referring to the 1873 Colt Single-Action revolvers these gentlemen had and/or carried.

In an effort to improve on my collection of early single-action revolvers, my search for a reproduction of the iconic 1873 Colt Single-Action Army (Cavalry) model revolver spanned over two years. Now, there are plenty of reproductions on the market, but this one had to be as close to the original as possible.

Uberti 1873 Colt Single-Action Army ‘Cavalry” Model.

I almost had one in my grasp. I had placed an order through a local gun store that was an Uberti dealer. Unfortunately, the revolver and a whole lot more stuff went down on the cargo ship during a storm. Davy Jones is now shooting that particular revolver.

Uberti, Srl. has been manufacturing single-action revolvers for quite some time (since 1959). Finally, a random search on the Davidson’s web site led me to Cimarron Firearms, who is a major importer of single-action reproductions. In the listing was a U.S. Cavalry model. I continued my search with some hesitation, because I was looking for an Uberti-made model and not a Pietta-made model. The Uberti would be as close to the original design as possible.

What unfolded before my eyes was the single-action revolver that I had been searching for, a “Cavalry” model of the 1873 Colt single-action revolver. I had purchased, some time ago, a version of the 1873 Colt SAA that was called the “Old West” model, a model that looks like it has seen better days, but actually was manufactured to look that way. I wrote a review of this fine revolver (https://guntoters.com/blog/2016/04/05/uberti-1873-cattleman-ii-old-west-revolver/), but still yearned for the ‘Cavalry” model because of its historical significance.

Note that the Colt 1873 Single-Action Army ‘Cavalry’ model is not available at the Uberti web site. It was originally (when I began looking) listed as the “Cattleman” revolver, but has now been replaced with the “Cattleman II” model. I’ll explain the differences between the two later in this review.

Colt offered a revolver, the 1872 Single-Action Army, which was nothing more than a cartridge-converted version of the 1871 open-top revolver, to the U.S. Army. You can read my review of Uberti 1872 SA Army replica at https://guntoters.com/blog/2015/12/10/uberti-1872-army-open-top-revolver-new-model-341350-review/. The 1872 Colt single-action revolver was rejected by the U.S. Army, because of its “frail nature” and asked for a more powerful caliber with a stronger frame.

After the rejection of the 1872 Colt SA Army, William Mason (not to be confused with Mason Williams of “Classical Gas” fame), the engineer who had designed the 1872 “open top” went back to the drawing board, borrowed some design from Remington, and submitted the 1873 Colt Single-Action Army for evaluation. The frame was stronger, it now had a top-strap, the action was slick as a sly Fox, and the rear sight was now part of the top strap rather than being grooved into the hammer. The big plus was that parts were interchangeable from revolver to revolver. The Remington, which I have always thought to be the superior revolver, was expensive to build in comparison the Colt Single-Action Army. The Colt was less expensive to manufacture and would cost the Army less to purchase.

The Colt Single-Action Army was later dubbed the “Peacemaker” revolver, and is known as “The Gun That Won the West.” Colt Single-Action Army was issued to the U.S. Cavalry with 7 1⁄2 inches of barrel length (with an overall length of 13 inches). A shorter, 5 ½” “Artillery” model soon followed. Later models were built with longer and shorter barrels for the civilian market, but the ‘Cavalry’ model was, what I consider, the “Papa” to the others.

Base Pin Screw (Early Model Colt).

The Uberti 1873 Colt Single-Action Cavalry model keeps to the first generation of the Colt design. Up until 1896, a screw (Base Pin Screw) was used to secure the Base Pin (cylinder rod), which was then replaced by a spring-loaded Base Pin Screw. The first generation of Colt single-action revolvers were manufactured until 1941 when manufacturing ceased to support the war effort. The second generation of Colt single-action revolvers did not pick up until 1956, and we are now in the third generation, which began in 1976. The Base Pin Screw needs to be checked periodically when firing the revolver (not unlike checking the loading tube cap on a Mossberg 500 shotgun). (Note: Uberti provides an extra Base Pin Screw.). The Base Pin Screw is a friction-fit into the Base Pin. Some would put a dab of Blue Loc-Tite on it to prevent out from backing out. I prefer not to. Also, finger-tight is enough to secure it for short shooting sessions. Do Not Over Tighten, or you might need a gunsmith to fix things when the screw snaps in half.

The 1873 Colt Single-Action Army was originally chambered for the .45 Colt cartridges. In fact, serial number 1 was in this chambering when it was finally located. Other calibers were also available. The model that I now have is in the original chambering, .45 Colt, as any Colt single action revolver should be (IMHO).

Let’s take a closer look at the Uberti 1873 Colt Single-Action Army “Cavalry” replica.

The Basics:

Description: CIM U.S. CAVALRY 45LC REV 7.5B

Brand: Cimarron

Model: U.S. Cavalry

Type: Revolver: Single Action

Caliber: 45LC

Finish: Blue

Action: Single Action

Stock: Walnut 1 Piece Grip

Sight: Fixed

Barrel Length: 7.5

Capacity: 6

Receiver: Case Colored Frame

Made by Uberti – Italy, U.S. Marked Frame; Old Model Frame, Cartouche on Grip

This particular model would be considered a “P” model (Pre-War, 1873 – 1941) replica. The beautifully finished case-colored frame blends well with the blued and polished barrel, cylinder, and back strap. The walnut one piece grip is finished well with a high-gloss coating, although I would prefer a natural finish that could be hand-rubbed, and blends well into the back strap.

One of the reasons that I wanted the Uberti version of this revolver is because Uberti kept the C.O.L.T click. As you pull the hammer rearward, there are four distinct clicks, C.O.L.T. until the hammer is fully cocked. This is a feature not found on most other ‘replica’ 1873 Colt SA revolvers by other manufacturers.

Modern single-action revolvers, like the Ruger and others, have hammer block safety and can be safely carried with all six cylinders loaded. The firing pin simply will not contact the primer of a cartridge unless the trigger is pulled. The Uberti does not have such a safety device, and approaches safety in a time-honored fashion with this model. However, that statement is not entirely true.

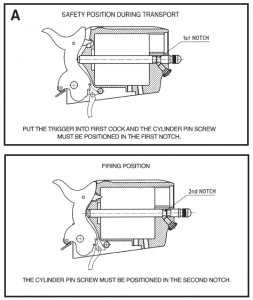

Cylinder Pin Screw Safety.

With the Uberti version, there are two notches in the Cylinder Base Pin. To prevent the hammer from contacting the primer of a loaded cartridge, the Cylinder Pin Screw must be positioned in the first notch of the Cylinder Base Pin. To be able to fire the revolver, the Cylinder Pin Screw is positioned in the second notch of the Cylinder Base Pin. Obviously, to transition from a non-firing mode to a firing mode, and vice-versa, the Cylinder Pin Screw must be unscrewed to accommodate the transition. Anyone with any modicum of knowledge regarding single-action revolver operation knows that there is only one “accepted” way (aside from keeping that darn trigger finger off of the trigger) to safely carry a single-action revolver like the Uberti. So, let’s talk about that “method.”

The safest way to carry the revolver is with only five cartridges loaded, as was done in the “Old West” unless you were preparing for battle on the battle field or the streets of Laredo, Texas. The hammer is brought back to half-cock, the loading gate opened, and this is the condition in which you load and unload the firearm. Then, load one, skip one, load four and shut the door. Pull the hammer all of the way rearward, support the hammer with your thumb, press the trigger while supporting the hammer, and lower the hammer on an empty cylinder. The firearm is now safe and cannot discharge a cartridge even when dropped. To put the firearm into action, simply cock the hammer to place the firing pin under a live cartridge. If this method can’t be worked out by the operator, the operator needs to hang up the single-action revolver in a nice display case and never touch it.

The difference in the version of the Uberti 1873 SA Army “Cavalry” model that I have, and the new Cattleman II models, is that the firing pin can be locked back into the hammer on the “Cattleman II” models. This prevents the firing pin from resting on a primer, should you load six cartridges. I have such a model in the 1873 Colt SA “Old West” model, but still prefer to simply load five and rest the hammer on an empty cylinder and not use the ‘new’ safety mechanism.

If you don’t know by now, allow me to enlighten you about pulling the trigger on single-action revolvers – any single action revolver. Never pull the trigger when the hammer is in the half-cock position, as it would be when loading or when performing a cylinder check for live cartridges. (Note: modern Ruger single-action revolvers are different; they can be loaded without cocking the hammer.) Always pull the hammer completely to the rear before pressing the trigger. Failure to do so could damage the internals of the revolver. Also, never leave the hammer in a half-cock position thinking that it would never fall on a live cartridge. Half-cock is not a position of safety. You don’t want to go off half-cocked now, do you? The single-action revolver is one of the safest firearms ever made, if you use some common sense when carrying or operating one. More dumb cowboys have probably shot themselves more than they got shot by others. Does the term, “Shooting oneself in the foot” ring a bell?

Let’s move on to other things.

Hammer, Rear Sight, and Loading Gate View. BIG .45 Colt Chambers!.

The front sight is rounded, narrow, and high on the barrel. The rear sight is a simply a notch cut into the top strap. The top strap is robust, but not as robust as that found on the Remington ‘flat top’ revolvers.

The trigger is excellent. With a trigger pull of 3 pounds and 10 ounces on this specimen out of the box, the rearward travel is short, and the break is clean. Everything was a little gritty at first, but that soon went away after a box of .45 Colt “Cowboy” loads were shot through it. This is a definite “keep your finger off of the trigger until you are ready to shoot’ firearm. There is a solid “Thunk” when the firing pin hits home.

Of course, as with any single-action revolver, don’t expect speed loading to be a top priority. The Extractor is long enough to adequately clear the chambers of empty cartridges. With a Ruger single-action revolver of later design, the operator simply has to roll out the loading gate to reload; the hammer no longer needs to be at half-cock. Not so with the Uberti single-action that uses old school technology. The hammer is brought back to half-cock, the loading gate is opened, and this is the condition in which you load and unload the firearm. Again, load one, skip one, load four and shut the door. It really makes you appreciate modern conveniences like speed-loaders and magazines.

There are several markings on the revolver worth noting. The left side of the frame is stamped with the patent information; Sept. 19, 1871 and July 3, 1872. Also stamped is the caliber of the revolver, which in this case is 45CAL. The serial number and F CO. 7 CAV is stamped on the bottom of the grip frame. The serial number is also stamped on the cylinder, the trigger guard, and just forward of the trigger guard on the frame. The top of the barrel is stamped Cimarron F.A. Co. FREDRICKSBURG, TEXAS AUBERTIITALY. There are also other stampings of manufacturers mark in various locations. There is also a faint cartouche stamped in to the grip on the left side.

“Open Type Button” Ejection Rod.

The 7 ½-inch barrel not only adds some velocity but also adds weight to the front of the revolver and improves accuracy. The sight radius is obviously longer. The revolver; however, is well-balanced in the hand. These revolvers were intended for Cavalry units, which mean that troops were mounted on horseback during that period of time. They were a bit slower to draw from a holster, but draw speed was not the first concern of the mounted soldier. Many of these 7 ½-inch barreled revolvers made it into the civilian market as well, and they also served as the foundation for the Bisley revolver, a target version of the Single Action Army (SAA) that was used for competition at a range in England, from where the Bisley Colt was named. The Bisley (produced from 1894 until 1915) is another target of my search for period replicas due to its history. But, that will be a review told later. The 7 ½-inch barreled 1873 Colt Single-Action Army revolver, in various barrel lengths and styles, was carried by both honest folk and characters of nefarious nature.

While I enjoy shooting modern firearms, I enjoy shooting a single-action revolver most of all, even modern ones like the Ruger. The Uberti single action revolvers, in their basic form, such as the 1873 Colt Single Action Army “Cavalry” model replica, takes me closer to the original as much as I can get. At the range, I am in no hurry to shoot them. I want to savor every short, light trigger pull. I shoot these one-handed and in a “target” stance. When they fire, the upward lift of the barrel and downward push of the grip in my hand soothes my soul – even if I can’t hit a damn thing with it. The revolver is not a tack driver, although you could drive tacks with some serious practice, or you are using the butt end to put up a “wanted” poster (on an empty chamber, of course). This particular Uberti 1873 Colt Single Action Army in ‘Cavalry’ form shoots high-left. It’s not something that I can’t compensate for, and these revolvers (even in original form) were not “target” guns. They were intended for point-shooting and the front sight merely used to ensure that that muzzle was pointed in the general direction of the target. It will; however, shoot a tight group at ten yards and I was able to place 5 shots to the head with ease – I just aimed at the neck.

Of course, these ‘replica’ revolvers are not intended for shooting full-power loads, although you can. I prefer the “Cowboy” loads to keep the wear and tear at a minimum. The original black-powder .45 caliber cartridge (for you silly millimeter types, that’s 11.43×33mmR) loads called for 28 to 40 grains (1.8 to 2.6 g) of black powder behind a 230-to-255-grain (14.9 to 16.5 g) lead bullet. These loads developed muzzle velocities of up to 1,050 ft/s (320 m/s). I like shooting “Cowboy” loads in the 700 to 800 fps range. What is ironic, of sorts, is that even Ruger recommends “Cowboy” ammunition in their single-action revolvers, with the exception of the Blackhawk and Super Blackhawk SA revolvers that will handle the heavier .45 Colt loadings.

Finally, let me mention the grip. The smooth grip makes for hanging on this revolver somewhat of a challenge with my mitt size. I would prefer the grip be without the protective finish and more indicative of the natural wood finishes of the originals (with a little work that can be done). However, with a grip high on the back strap, I can fit all fingers around the grip. These revolvers actually warrant the pinky finger beneath the grip for additional support. The pinky finger beneath the grip helps to mitigate the grip plowing in the hand by a large margin. The single-action revolver, by design, was meant to roll in the hand. This places the hammer closer to the cocking thumb after recoil. As the revolver is cocked, the barrel is rolled onto the target. But, I have no problem reaching the hammer with either a ‘high’ or ‘low’ grip. I do; however, prefer a ‘high’ grip.

Finally, let me mention the grip. The smooth grip makes for hanging on this revolver somewhat of a challenge with my mitt size. I would prefer the grip be without the protective finish and more indicative of the natural wood finishes of the originals (with a little work that can be done). However, with a grip high on the back strap, I can fit all fingers around the grip. These revolvers actually warrant the pinky finger beneath the grip for additional support. The pinky finger beneath the grip helps to mitigate the grip plowing in the hand by a large margin. The single-action revolver, by design, was meant to roll in the hand. This places the hammer closer to the cocking thumb after recoil. As the revolver is cocked, the barrel is rolled onto the target. But, I have no problem reaching the hammer with either a ‘high’ or ‘low’ grip. I do; however, prefer a ‘high’ grip.

As a side note regarding the grip; the grip was actually a carry-over from the 1851 Navy Colt, which was a bit wider than those that followed it, like the 1860 Army and 1871 Army.

All is not perfect!

I would love to say that the Uberti 1873 Colt Single-Action Army ‘Cavalry’ model is perfect, but I can’t say that.

Before shooting any firearm for the first time, you should do a thorough inspection and cleaning, and that’s when I found the issue. Firearms from Uberti are manufactured to close tolerances, and are much tighter than the original single-action revolvers.

When I was installing the cylinder, I noticed that it was not as easy to install as other single-action revolvers that I have. Usually, the cylinder just rolls into place and only takes minor movements to align with the Base Pin. That wasn’t the case with this revolver. Once I did get everything into place, I rotated the cylinder and noticed it binding quite heavily at one spot in the rotation. To illustrate the tight tolerances of this revolver, the “Flash Gap,” the gap between the forcing cone (the end of the barrel closest to the cylinder) and the face of the cylinder is less than 0.0015-inch, which is the thinnest feeler gauge that I have. On average, the “Flash Gap” is around 2 to 4 thousands of an inch (0.002 to 0.004) in most modern revolvers. Where was the binding occurring?

It is usually reasonable to assume, especially in a new revolver like this single-action, that the cylinder star (ratchet) is the culprit. The cylinder star is what rides against the frame at the rear. The “Hand” is what engages the cylinder star to rotate the cylinder when the hammer is pulled rearward. Any binding places excessive strain on the “Hand” when traveling upward to turn the cylinder. In this case, the cylinder star was binding only in one spot and near the loading gate.

Using a fine Emory board, I began smoothing the face of the cylinder star. The problem could have been bluing thickness, a bit of flash left over from the machining process, or a high spot as a result of the same process. Polish a bit, check for fit. (Note: If this happens, it may be necessary to repeat this process until no more binding is occurring.) When I finished, there was still a slight hint of binding, but nothing that rotating the cylinder would not fix. And, that’s exactly what I did. Rotate, rotate, and then rotate the cylinder some more with the hammer in the half-cock position, rolling my hand across the cylinder. There is some kind of perverse satisfaction listening to the locking lugs of the Cylinder roll across the Cylinder Stop during free rotation. All in all, I probably rotated the cylinder enough times to have shot close to 1,000 cartridges.

I also use “Snap Caps” to check for smoothness during cylinder rotation. Plus, they are great to use for “Dry Fire” practice.

CAUTION! Never, ever (unless you are a gunsmith who knows exactly what you are doing) touch the contact points where the cylinder star (ratchet) and hand meet. This could affect the timing of the revolver that could result in chamber misalignment with the barrel, which could cause very undesirable results for the revolver – and possibly to you as the operator of the revolver. If you hear the fourth cocking notch engage the sear, but the cylinder is not locked into place, the revolver has a problem.

The revolver, by the way, locks up tighter than a drum. There is barely perceptible play in the cylinder sideways (tight tolerance between the cylinder locking lugs and the cylinder stop) when locked up and forward/rearward play does not exist.

As a side note, the close tolerances of these revolvers may require you to wipe (or brush) the face of the cylinder clean after every few cylinders of ammunition fired. This is especially true with black powder (percussion) revolvers that are especially noted for their dirtiness and where powder residue would build up on the face of the cylinder, which would eventually bind-up the cylinder to a point where the cylinder would either be too difficult to rotate or would bind up completely. Never force a cylinder into rotation.

In Closing:

If I said that there wasn’t a bit of nostalgia in shooting these Uberti replicas, I would be lying. As someone once said, “There’s a little cowboy in all of us.” Shooting a replica like the Colt Single Action Army “Cavalry” model, as well as my other Uberti single-action revolvers, brings out that little cowboy in me, even though some of the Chippewa ancestors (on my Mother’s side) might cringe at that thought.

The Uberti 1873 Colt Single-Action Army in “Cavalry” form is an excellent representation of the original, with the exception of the Cimarron “Billboard” on the top of the barrel. The firearm feels great in the hand and is an excellent shooter.

If you are considering moving to a slower lane of shooting, check out the Uberti line of single-action revolvers, or possibly even a long gun or revolving carbine, or a…

RESOURCES:

Quality Replica Guns of the Old West: https://www.uberti-usa.com/

How single-action revolvers work: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I8NSDCNTRaQ

Difference between Uberti and Pietta reproduction revolvers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtJAYVVH464

![]()

2 Responses to The Old West Lives On! Uberti 1873 Colt SA Army (Cavalry) Reproduction