—by M1911A1—

1. The One That Got Away:

Martin B. Retting, the large and prosperous gun shop in Culver City, California, used to be located in West Hurley Village, in Ulster County, New York. In the summer, I used to hitch-hike out from New York City to the dairy-farm areas on the west side of the Hudson River, and find summer jobs as a dairy-farm hand. Thus, I became acquainted with Retting’s shop while Mr. Retting was still alive.

Mr. Retting wasn’t the nicest person, but he always had a full stock of antique and almost-antique, military and historical guns for sale. He published a line-drawing-illustrated catalog which I picked up every year, so I could spend the winter drooling over what I might be able to buy during the next summer. I once bought a really nice, unmodified, .30-40 Krag from him at a very reasonable price. I learned cartridge reloading on that Krag, and even took it deer hunting twice. (Later, I stupidly modified it to a sporter, and then traded it to Dick Bard for a Manton muzzle-loading shotgun, but that’s another story.)

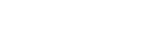

One winter in, I think, 1954, I saw an item in Retting’s catalog (dated 1953) which truly excited me. He showed a tantalizing line drawing, and described it as (paraphrased) a flintlock Kentucky long rifle that had been modified by the addition of a reduced-size Hall breechloading mechanism, and converted to percussion. “…There is an excellent possibility that this is the original rifle made by Hall for the military trials.” It led to the Hall breechloader of 1819, the first breechloader in US service, as manufactured at Harper’s Ferry.

I did my due-diligence research and, as far as I could make out, Retting’s catalog description was accurate. But, since there was no mention of provenance, Retting had it listed for $350.00. Even in 1954, this was a bargain, since the gun could turn out to be of inestimable value.

At the time, between high school and college, I held a full-time job as a Clinic Clerk in a New York City charity hospital. I was making the princely sum of 75¢ an hour. So I went to my very well-to-do parents, showed them the ad and my research, and tried to strike a bargain. I pledged my entire income, both summer and winter, for as long as it took to earn the $350.00 price of this modified Kentucky rifle that might be Hall’s trials model. To make a long story a little shorter, my parents’ response was a resounding “No!” “Think of how long it will take you to earn $350.00,” they said, among other things.

Shortly after this disappointment, I left home forever and took myself off to Los Angeles, California. At about the same time, Martin B. Retting moved his gun shop from New York State to Culver City, California, a southwestern suburb of Los Angeles.

Perhaps for tax purposes, perhaps to lighten his inventory, perhaps because it still hadn’t been properly provenanced, Retting donated the modified Kentucky for which I still slavered to the Los Angeles County Historical Museum. And there I saw it again, in a display case, finally properly provenanced by museum staff, and placarded as (paraphrased) “Hall’s Model for his Innovative Breech-Loading Rifle in US Service.” It was, of course, literally priceless.

When my mother came to visit me, a couple of years later, I made sure to take her to the L.A. County Historical Collection, and then made certain that she got to see the gun and its placard.

And, yes, she remembered it.

2. The Long Rifle:

The lower rifle is the subject of this personal-history note. It’s an original Kentucky rifle, made in Pennsylvania in the early 1800s and later converted to caplock. The upper rifle was built by me, in the 1980s, mostly from Dixie Gun Works parts. The leather and horn work is mine.

During my formative years, I avidly read James Fenimore Cooper’s “Leatherstocking Tales,” about a long-rifle-armed woodsman who lived most of his life in middle-western New York State. Cooper’s stories, written in the 1830s, covered the early years of the US, from the French and Indian War of 1757 through the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1803.

Cooper’s prose is still, today, the paradigm of turgidity. Sam Clemens (Mark Twain) wrote a wonderfully funny critical essay on Cooper’s writing style, which is well worth your time to find and read. Look for Twain’s “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses.” But turgid as Cooper’s prose may be, the contents of his stories are, even today, both exciting and interesting. They awakened in me a deep and avaricious need for a frontiersman’s long rifle just like the one carried by Cooper’s hero.

I write, now, about approximately the same time as the “Hall’s rifle” story, above. At this time, Mr. Robert Abels kept an antique-arms store on Madison Avenue in mid-town Manhattan. Abels dealt in very high quality antique weaponry, and, during the winter, I was a much-too-frequent visitor to his shop. Mr Abels was a gruff sort, and he made it plain that if I wanted to keep visiting his stock, I would have to buy something. I explained my financial situation to Mr. Abels, and I told him what I was looking for. He had several very-high-quality Kentucky rifles in stock, all of which he allowed me to handle, but, of course, they were terribly expensive, and well out of my reach.

But, one day, I walked into the little shop and found a wide grin on Mr. Abels’s face. “I have exactly what you’re looking for,” he said. “You can afford it, and I want you to buy it. And then I want you to go away.”

He reached behind a display cabinet and pulled out an old and raggedy muzzle-loading rifle. It was in poor condition, and had been “ridden hard and put away wet,” but it was a real Kentucky rifle. And Mr. Abels guaranteed that it was safe to shoot, too. There was no discussion about price. I could indeed afford to buy it, so that’s what I did. I carried it home, open and unwrapped, in the New York City subway. (Try that, today.) I had to do some repair work on it, to make it completely functional, but it did indeed shoot, and pretty well, too. I took a deer with it, a couple of years later.

It took me a long time to work out its provenance, and maybe even its maker, and then even longer to tease out its value. It was a cheaply-made rifle, even in its day, but it had been built strong, to survive hard use. Its wood was real maple, but the stock’s tiger-stripe grain had been artificially applied by spirally wrapping it in string, and then setting the string on fire.

But I finally figured out that Mr. Abels was a lot less gruff and forbidding than he had seemed to be. He had sold me that rifle for probably less than he had paid for it, because he knew that I wanted it so very much. It had been almost a gift! I am still sad that, by the time that I’d learned the true facts, I was in California, and Mr. Abels was dead.

I still have the rifle. It hangs over our library fireplace, ready for use, just as it would have in a frontier home in middle-western New York, during the early 1800s.

![]()

3 Responses to The One That Got Away…and The One That Didn’t Personal History